I have always been drawn to history, especially the way our understanding of the past often rests on a surprisingly small number of surviving written sources. In the case of Christopher Columbus, the original ship logs from the first voyage no longer exist. What we have instead are copies, summaries, and transcriptions preserved in the journals and correspondence of others, including versions recorded and translated decades later. These surviving texts, while imperfect, provide a rare day by day narrative of the voyage itself, including distances sailed, compass headings, weather conditions, and Columbus’s own private estimates alongside the figures he reported to his crew. Using the Diario de a bordo and related contemporary compilations and translations, including multiple Spanish and English editions of the first voyage journal and selected letters, it becomes possible to reconstruct the crossing through dead reckoning rather than illustration alone. By combining reported leagues traveled, noted course changes, and observations of magnetic compass behavior recorded in these primary sources, a plausible daily track can be estimated. This project begins that reconstruction by translating the written record into a KML map, allowing the voyage from departure to landfall to be examined one day at a time through the evidence Columbus himself left behind.

First Voyage

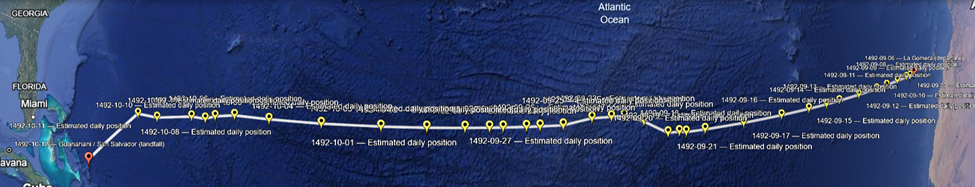

This KML represents a careful reconstruction rather than a claim of exact precision. It shows daily dots marking where Columbus would plausibly have been based on the leagues per day recorded in the log and the west, west southwest, and west northwest course changes he explicitly describes. It includes fixed anchors at La Gomera as the known departure point and Guanahani as the known landfall, connected by a continuous track line so the viewer can visually inspect drift, curvature, and pacing across the voyage. The file documents its assumptions clearly, including the use of one league as approximately three nautical miles, bearings treated as approximate true bearings derived from magnetic courses, and the absence of usable longitude fixes in 1492, which means uncertainty naturally increases in the mid Atlantic. Periods of calm and course changes guided by birds are preserved rather than smoothed away. When viewed, the track bends gently instead of forming a straight line, the days from October sixth through October tenth show noticeable course instability that aligns with crew anxiety and bird sightings, the final approach aligns logically with the Bahamas rather than Cuba or Florida, and the daily pacing feels human, with fast days, slow days, and pauses. Overall, this reconstruction is more historically honest than most published maps.

To actually see the reconstruction, we load the KML into Google Earth on the web. Open this in your browser:

https://earth.google.com

From there, go to Projects, choose Open or Import, and upload the KML file you downloaded from this chat. Once it loads, you will see the voyage as a connected track with dated dots. Clicking each dot opens the description text for that day, so you can follow the crossing step by step and visually inspect how the route curves, where it speeds up or slows down, and how the day by day pacing matches what the log describes.

Second Voyage

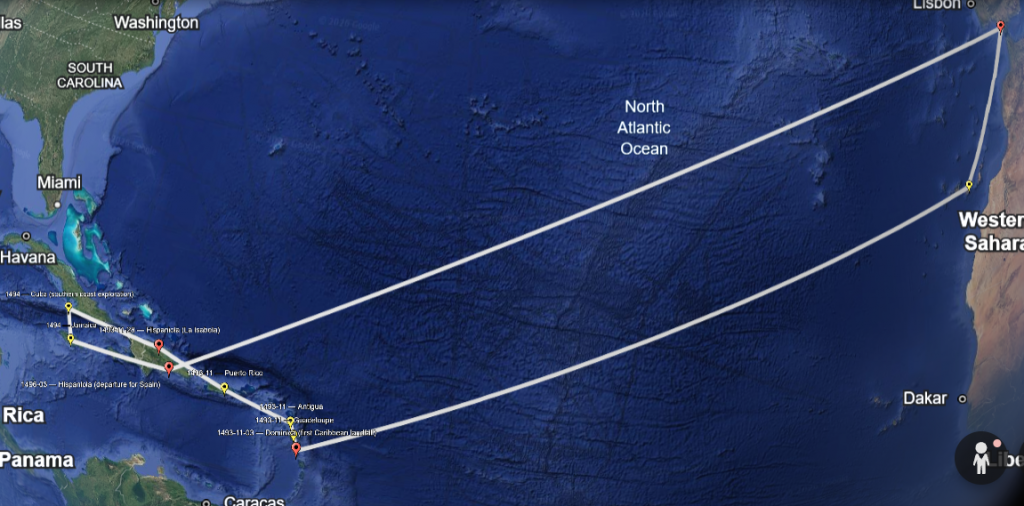

The second voyage of Christopher Columbus is documented far more broadly than the first, but the records are also more fragmented. Unlike the 1492 crossing, there is no single continuous ship’s diary that survives intact. Instead, the movement of the fleet must be reconstructed from a combination of letters, journal excerpts, official reports, and contemporary accounts written by Columbus himself and by those who sailed with him. These sources do not always agree in detail, but they consistently name places, dates, and sequences of movement that allow the overall path of the voyage to be traced with confidence.

This reconstruction was created by identifying every dated or clearly implied location where Columbus is attested to have been present during the second voyage, beginning with the departure from Spain in 1493 and ending with the return in 1496. Each point plotted in the KML corresponds to a place explicitly named in the surviving sources, such as known departures, landfalls, island visits, and extended stays. Rather than inventing daily positions where no distances or headings are recorded, the map anchors itself to these historically supported locations and connects them in chronological order to show the flow of the voyage.

The result is an anchored track rather than a dead reckoning line. This approach avoids artificial precision and reflects how the second voyage actually functioned. By this point, Columbus was no longer searching blindly across open ocean but moving deliberately between known islands and colonial centers. Navigation relied heavily on visual landfall, short sea passages, and repeated routes, which makes named locations more reliable than inferred daily distances. Where the historical record is silent or vague, the map remains intentionally conservative.

This KML is therefore best understood as a geographic index of the second voyage rather than a continuous navigational trace. It shows where Columbus was, when he was there, and how the expedition expanded outward from the initial Atlantic crossing into sustained movement across the Caribbean. When viewed alongside the first voyage reconstruction, it highlights the shift from uncertainty and exploration to repetition, logistics, and occupation, using the surviving documentary record as its sole guide.

Sources used for KML generation of 2nd Voyage:

- Select Letters of Christopher Columbus, which preserves Columbus’s surviving correspondence to the Spanish Crown and others, including letters written during and immediately after the second voyage that reference specific locations, dates, colonial activities, and movements between the Canary Islands, the Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Cuba, and Jamaica

- Letters from Christopher Columbus to Ferdinand and Isabella (1493–1496), transmitted as official reports and later copied into archival collections, providing dated references to departures, landfalls, settlement efforts, and returns that anchor Columbus to identifiable places even when navigational details are absent

- Columbus’s memorials and administrative reports often labeled Relación, which summarize discoveries, colonial conditions, and travel sequences during the second voyage and survive through later copies rather than original manuscripts

- The letter of Diego Álvarez Chanca, an eyewitness account written by a participant in the second voyage that describes the Atlantic crossing, first Caribbean landfall at Dominica, early island exploration, and conditions on Hispaniola, serving as one of the most reliable independent confirmations of dates and locations

- The narrative account of Michele da Cuneo, an Italian nobleman who sailed on the second voyage and later recorded his experiences, providing corroboration for island sequences and movements while requiring careful critical reading

- Historia de las Indias by Bartolomé de las Casas, which preserves summaries and quotations from documents that no longer survive and records chronological movement during the second voyage based on sources available to Las Casas in the sixteenth century

- Vida del Almirante by Fernando Colón, written using family papers and now lost records, offering sequencing and contextual detail for the second voyage, particularly regarding Hispaniola and the wider Caribbean

- Historia General y Natural de las Indias by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, which compiles early testimonies, official documents, and firsthand accounts that preserve locations, dates, and movements associated with the second voyage

This combined documentary record forms the basis for the anchored KML reconstruction, relying on named places and dated attestations rather than inferred daily navigation where the sources remain silent.

Third Voyage

The third voyage of Christopher Columbus is reconstructed differently from the first two because the surviving record emphasizes events and locations rather than continuous navigation. No complete ship’s log survives for this voyage, and the sources that do exist consist primarily of letters, official reports, and later historical compilations that record where Columbus was at specific moments rather than how he traveled day by day. To build this KML, every dated or clearly implied location mentioned in these documents was identified, beginning with the departure from Spain in 1498 and ending with Columbus’s forced return in 1500. Each placemark represents a place where Columbus is explicitly documented to have been present, such as known staging points in the Atlantic, first landfall at Trinidad, exploration of the Gulf of Paria and the South American mainland, extended residence on Hispaniola, and his arrest at Santo Domingo. These anchored locations were then ordered chronologically and connected to show the overall movement of the voyage without imposing artificial precision where the sources are silent. This method reflects the historical reality of the third voyage, which was defined less by open ocean navigation and more by coastal exploration, settlement, and political collapse, and allows the map to remain faithful to what the documentary record can actually support.

Here is the single long bullet list of sources used for reconstructing Christopher Columbus’s Third Voyage (1498–1500), written consistently with the earlier voyages:

- Select Letters of Christopher Columbus, which includes letters written by Columbus to the Spanish Crown during and after the third voyage, describing his route to the south, first landfall at Trinidad, exploration of the Gulf of Paria, his belief that he had reached a continental landmass, and the deteriorating political situation on Hispaniola

- Letters from Christopher Columbus to Ferdinand and Isabella (1498–1500), preserved through later copies and archival compilations, which provide dated references to departures, landfalls, coastal exploration near South America, and Columbus’s reports of unrest and resistance to his authority

- Columbus’s memorials and formal reports commonly referred to as Relación, which summarize discoveries, geographic observations, and administrative actions taken during the third voyage and survive through later transcription rather than original manuscripts

- Historia de las Indias by Bartolomé de las Casas, which preserves summaries of now lost documents and provides a chronological account of the third voyage, including Columbus’s movements around Trinidad, the Paria coast, and Hispaniola

- Vida del Almirante by Fernando Colón, written using family papers and records that no longer survive, offering sequencing and contextual detail for the third voyage and Columbus’s changing perception of the lands he encountered

- Historia General y Natural de las Indias by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, which compiles early testimonies, official correspondence, and firsthand accounts that record locations, dates, and events associated with the third voyage

- Official Spanish administrative records relating to Francisco de Bobadilla, including orders, reports, and correspondence concerning the investigation of Columbus’s governance on Hispaniola, his arrest in 1500, and his transport back to Spain, which anchor the final phase of the voyage to specific places and dates

Together, these documents form a fragmented but overlapping record that allows the third voyage to be mapped through anchored, historically attested locations, avoiding conjectural daily navigation while remaining faithful to the surviving evidence.

Fourth and Last Voyage

The fourth and final voyage of Christopher Columbus survives in the historical record primarily through letters, reports, and later chronicles rather than through a continuous ship’s log. By this stage of his career, Columbus was no longer engaged in open ocean discovery but in deliberate coastal exploration, repeated landfalls, and prolonged periods of enforced immobility. To construct this KML, all surviving documentary references that place Columbus at a specific location during the years 1502 to 1504 were collected, including departure and return ports, named island landfalls, coastal regions along Central America, and the extended stranding in Jamaica. Each of these locations is supported by contemporary correspondence or early historical compilations that preserve the sequence of events even where navigational detail is absent.

The mapping approach used here is intentionally anchored rather than speculative. Instead of attempting to infer daily positions or routes where no distances or headings are recorded, the KML plots only those places where Columbus is documented to have been present and connects them in chronological order. This method reflects the character of the fourth voyage itself, which was shaped by storms, ship deterioration, political exclusion from Hispaniola, and long periods without movement. Coastal segments along Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and the Veragua region are shown as sequential stops rather than continuous tracks, while the Jamaica phase is represented as a fixed location spanning many months. The resulting map presents the fourth voyage as it appears in the historical record, grounded in documentary evidence and free from artificial precision, allowing the geographic scope and narrative progression of Columbus’s final expedition to be examined with clarity and restraint.

Here is the single long bullet list of sources used for reconstructing Christopher Columbus’s Fourth Voyage (1502–1504), consistent with the earlier voyages and grounded in the surviving documentary record:

- Select Letters of Christopher Columbus, which contains letters written by Columbus during and after the fourth voyage describing his final expedition, his exclusion from Santo Domingo, coastal exploration along Central America, the worsening condition of his ships, and his prolonged stranding in Jamaica

- Letters from Christopher Columbus to Ferdinand and Isabella (1502–1504), preserved through later copies and archival compilations, which provide dated references to departure from Spain, encounters in the Caribbean, reports of storms and ship damage, appeals for assistance while stranded, and his eventual return

- Columbus’s memorials and reports commonly referred to as Relación, which summarize discoveries, hardships, and decisions made during the fourth voyage and survive only through later transcription rather than original manuscripts

- Historia de las Indias by Bartolomé de las Casas, which preserves narrative summaries and quotations from now lost documents and provides a chronological account of the fourth voyage, including the Central American coast and the Jamaica stranding

- Vida del Almirante by Fernando Colón, written using family papers and records that no longer survive, offering sequencing and contextual detail for the final voyage and Columbus’s declining authority and health

- Historia General y Natural de las Indias by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, which compiles early testimonies, official correspondence, and firsthand accounts that record locations, dates, and events associated with the fourth voyage

- Contemporary Spanish administrative correspondence and royal directives, including orders, responses, and reports related to Columbus’s authority, restrictions placed upon him during the voyage, and arrangements for his rescue and return, which anchor the final stages of the expedition to specific places and dates

Together, these sources form a fragmented but overlapping record that allows the fourth voyage to be mapped through anchored, historically attested locations, avoiding conjectural navigation while remaining faithful to what the documentary evidence can actually support.